Don't forget your old shipmates

The enduring charm of Master And Commander (NB: contains spoilers for those who haven't seen it)

Master And Commander: The Far Side Of The World passed me by on its original cinema release, in November 2003. Which is odd, in retrospect, because I have always loved stories set in the golden age of fighting sail, and cinematic treatments of such tales are not exactly ten a penny. Quite apart from any considerations of cultural fashion, maritime swashbucklers are expensive to make. The eight episodes of the fairly decent Hornblower series that aired between 1998 and 2003 reportedly set ITV back tens of millions of pounds, but even so - and allowing for changed expectations two decades on - the special effects and general mise-en-scène look a bit undercooked in places. The 1995 pirate yarn Cutthroat Island cost nearly $100m, and its disastrous performance at the box office1 presumably made the Hollywood moneymen somewhat wary of taking any further risks on scripts involving cutlasses, cannonballs and close-reefed tops’ls. The greenlighting of 2003’s other naval adventure featuring a captain called Jack, the tiresome Pirates Of The Caribbean, is a point against this assumption, but that was doubtless considered a pretty safe bet, based as it was on a much-loved Disney World attraction.

Anyway, I digress. I came to Master And Commander on DVD, on a winter evening in early 2005. I was unfamiliar with the books, despite having devoured somewhat similar sagas like CS Forester’s Hornblower and Dudley Pope’s Ramage, but I was immediately enthralled by the film’s opening scene. Director Peter Weir sets out his stall with a beautifully framed shot of topmen scrambling silently up the ratlines in the moonlight. Soon afterwards, the camera descends the companionway to give a claustrophobically realistic idea of what it would feel like to be on the crowded gundeck of a sixth-rate frigate2, only about thirty feet wide and only about the length of two cricket pitches from stem to stern.

And it gets better and better over the next two hours. No wonder there remains an enthusiastic and knowledgeable fanbase, twenty years on. The attention to detail is joyously consistent, from the sound design to the costumes to the Catholic ship’s doctor Stephen Maturin not joining his mostly Protestant shipmates in the concluding doxology to the Lord’s Prayer3.

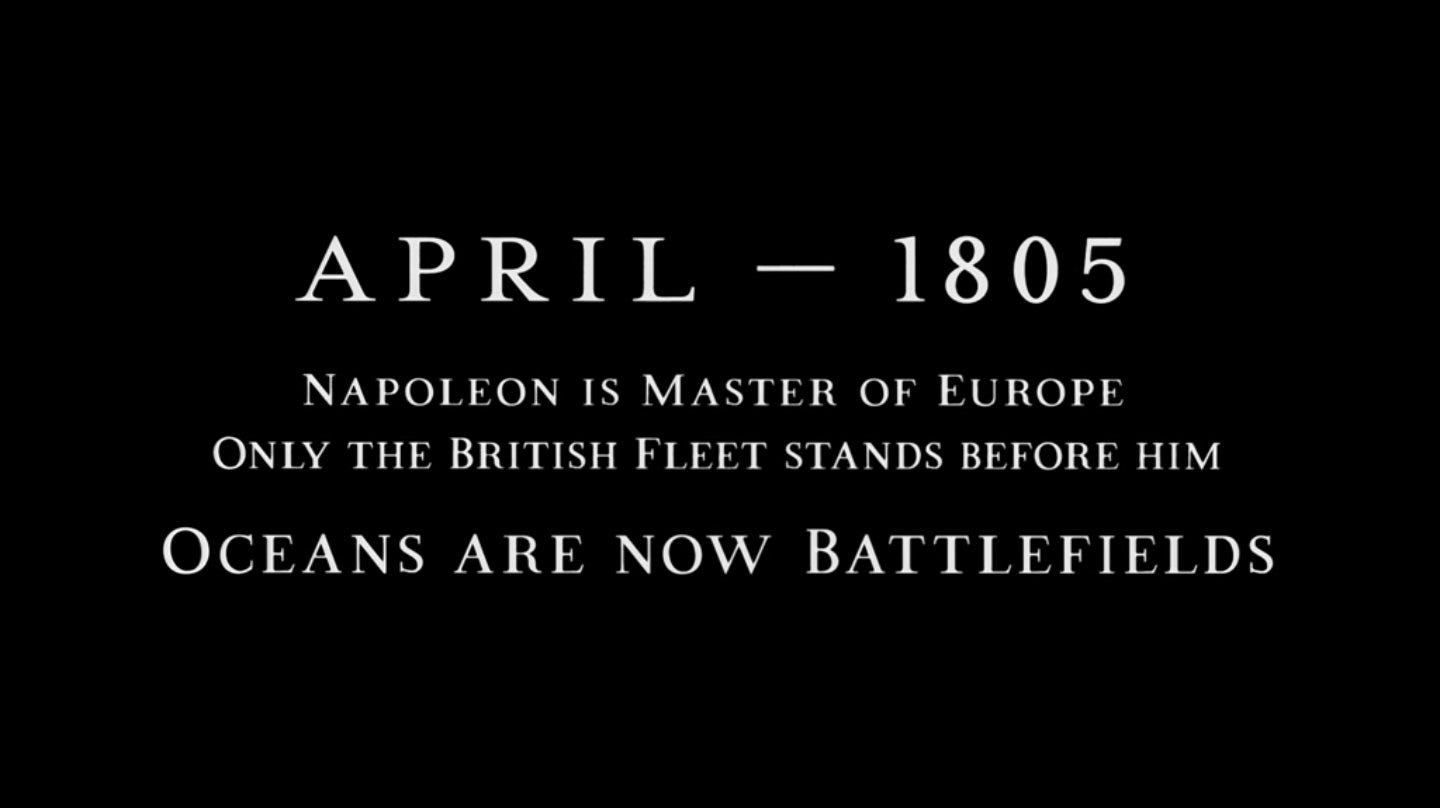

The story is simple. In the year 1805, HMS Surprise - 28 guns, 197 souls, Captain John “Lucky Jack” Aubrey commanding - is under orders to sink, burn or take as a prize the French privateer Acheron, bound for the Pacific to attack British shipping there.

Several gripping action set pieces follow; a frightening passage round Cape Horn in a hurricane, as well as a series of ship-to-ship fights. We see the terrible damage done to men by flying wood splinters, and the chaotic brutality of the close-quarters fighting engaged in by boarding parties. But we also see that combat, while horrific and terrifying, is an infrequent interruption to the Surprises’ normal routines, which have their own rhythm and fascination.

It is this glimpse of the pattern of shipboard life - the small community of men working together skilfully to achieve a mission - that holds part of the key to the film’s enduring popularity. I don’t want to get too deep into the Crisis Of Masculinity discourse. However, it seems fairly uncontroversial to note that many men in the early twenty-first century are - perhaps unknowingly - nostalgic for a time when numerous clear pathways were available to form strong bonds with other men, when they could achieve mastery, comradeship and the admiration of their peers, not necessarily through military service but through other forms of skilled mass labour or other forms of male association. “Every man thinks meanly of himself for not having been a soldier, or not having been at sea,” as Dr Johnson put it (admittedly in the eighteenth century). Even for those men in our own time who decide to cultivate a more traditional path, it is very hard to do so in the way that our grandfathers did, because by the simple act of choosing to be More Masculine, we are adding a layer of performance to our existence. This would have been mostly alien to our forebears.

Master And Commander, then, appeals because Jack Aubrey and his men by and large do not seem to have this problem of doubt and self-consciousness in their masculinity, and in their “male bonding”, however hard their lives are in other respects. Patriotism and national pride are normal and healthy - at one point Jack rallies them for battle by declaring “this ship is England” and asking rhetorically if they want to “call that raggedy arse Napoleon your king?” Emotional restraint of a kind that is distinctly unfashionable in 2023 comes naturally to them, heightening the dramatic impact of the miseries and misfortunes that they endure. Twelve-year-old Lord Blakeney undergoes the amputation of his arm (sans anaesthetic) with barely a sound, and the scene in which Jack visits him in the sick bay afterwards is all the more moving because of what goes unspoken. Russell Crowe makes a great job of showing Jack’s blend of pride, concern and quasi-paternal affection, behind the official reserve that his rank and status demand.

So the film portrays masculine virtues in a sympathetic way. Jack Aubrey is heroic, and that heroism is entwined with his being an unabashed man’s man - strong, funny, courageous, masterful. But every man on board the ship has his own responsibility and area of expertise, however limited. From ordinary seaman or cook’s mate right up to the first lieutenant, each has an arena in which he can and must excel for the tangible benefit of the whole. Meanwhile, Jack may get the big cabin with the nice view, but he must also make the big decisions. It is his call to follow the Acheron into the Pacific, round the Horn. It is he who must give an order to cut away trailing wreckage of masts and spars, and so doom to certain death Warley, who has fallen overboard, in order to prevent the entire ship from foundering. It is he who must make the final decision to engage the Acheron, a bigger and more powerful foe, and he who must “stand tall on the quarterdeck” without flinching or ducking when the shooting starts.

The loneliness of command - a commonplace of sea stories - is tempered in Master And Commander by scenes of camaraderie, most notably when Jack invites the officers to dine with him. The military men have a little good-natured fun at the expense of the inveterate landsman Stephen, but it is without malice. Fundamentally, he is one of them. He is part of their communal defiance of a hard & lonely life. One of the very best scenes in the whole film is when they break into the old naval song Don’t Forget Your Old Shipmate. It lasts less than a minute, but we get several subtle character moments. Stephen’s inherent reserve breaks down in the face of the unfeigned jollification. Blakeney, looking somewhat the worse for drink, also hesitates to join in, before finding his voice, an allusion to his ongoing initiation into the sphere of adult masculinity (something else to which modern boys lack reliable access). Jack, for his part, hands a glass of port to Killick, a sign of his generosity and care for his men. As the song ends, we cut to a long shot of the Surprise, alone in the dark on the old grey widow-maker.

All that said, this is too intelligent a film to offer us a merely one-sided view of male fellowship. The storyline featuring Midshipman Hollom asks us to reflect on what this unforgiving kind of world was like for a man who is expected to lead but lacks the confidence or the ability to do so. Hollom is nearly thirty, far older than most midshipmen, and has twice failed to pass for lieutenant, hampered by his diffidence and hesitancy. Calamy, another mid, treats him harshly, and he is mistrusted by the crew. In an interview with Jack, the captain firmly but kindly criticises Hollom’s belief that he can, or should, try to make the men like him. “It's leadership they want…find that within yourself, and you will earn their respect.” But even as he dismisses the man, Jack seems to realise that it is very hard to teach the kind of instinctive swagger and authority that he himself possesses. Hollom’s story ends unhappily. Weir does not ask us to burn with anger at the injustice of it all, or to condemn the customs and conventions of two centuries ago. He simply presents us with a poignant human tragedy.

***

One of the central concerns of the film is the relationship between Jack and Stephen4. The screenplay does a pretty good job of filling out their respective characters, although the books - twenty of them, totalling by my rough estimate over a million and a half words - have the time and space to do so more richly and deeply5. Their relationship is of a kind not commonly seen or celebrated in modern culture - a deep and intimate male friendship, founded in a mutual love of music and an appreciation for the virtues and strengths of the other.

Jack, as noted above, is brave and big-hearted, a born sailor and a born leader. He is not an intellectual but nor is he a philistine: he and Stephen play music together - he the violin and Stephen the cello - to the comic disgust of Preserved Killick, the captain’s steward. “Here we go again. Scrape, scrape”. Stephen is quieter than his friend, restrained and academic in temperament and a liberal in politics. He too is courageous, however, conducting surgery on himself after being wounded in a shooting accident6.

He is also a political radical - his background is barely eludicated on screen, but the books explain that he is a veteran of the United Irishmen’s rebellion of 1798, who nevertheless works as a spy for London because he loathes the tyrant Napoleon even more than he loathes British rule in Ireland. That radicalism leads to his confronting Jack with an objection to the flogging of a seaman, Nagle, who failed to salute Hollom. His dismissive attitude towards naval tradition - something very close to Jack’s straightforward Tory heart - sets off a quarrel, focused on the relative importance of freedom and authority in human affairs.

Stephen criticises the then-common practice of impressment, and expresses sympathy for mutineers who resist the sometimes wretched conditions and harsh discipline of the Royal Navy. “There is no disdain in nature”, is his response to Jack’s observation that the natural world - of which Stephen is a keen and knowledgeable student - is full of hierarchy.

Jack is reluctant to flog Nagle, who earlier helped to cut away the debris that was causing the ship to capsize, despite his close friendship with Warley. Nevertheless, Jack explains to Stephen that he “can only afford one rebel”, an understandable impulse given the size of the “little wooden world” of HMS Surprise and their vast distance from home (some ten thousand miles or more of sailing at this point in the story). “Men must be governed”, he retorts to Stephen’s criticism of the crudity of naval punishment. “You’ve come to the wrong shop for anarchy, brother”, is his parting shot to the doctor; we then cut immediately to the maindeck grating, where the unfortunate Nagle is kissing the gunner’s daughter.

The argument is not resolved because it is in essence unresolvable. Both men are right. Jack’s insistence on the necessity of order and obedience for the effective operation of the navy, and of society more widely, and Stephen’s preference for liberty and the prerogatives of the individual, are each powerful and compelling. It is the eternal dispute between the conservative and the liberal, particularised in a specific situation and yet endlessly relevant.

There is so much more that could be said about why Master And Commander is a great piece of filmmaking. As in most classic naval stories, the sea itself is a character - untrustworthy and changeable, an ever-present threat to both pursuer and quarry, whose antagonism with each other is intertwined with their mutual antagonism towards the sea. And I have barely touched on the excitement of the climax, the superb soundtrack, the humour, and its emphasis on Stephen’s passionate devotion to natural philosophy (what we would now call naturalism). The subplot concerning his desire to visit the Galapagos Islands - including a cheeky intimation that he might pre-empt Darwin by thirty years - delights me anew every time I watch.

But I’ll leave it there for now.

Every man to his rope or gun.

According to Wikipedia, the final box office take for Cutthroat Island was $10m. Personally I seem to remember quite enjoying it, but then I think I last watched it on TV on a Saturday night in the late 1990s, so take that with a pinch of salt.

At the time of the Napoleonic Wars, Royal Navy ships were categorised by how many cannon they mounted, from the mighty first-raters with over 100 all the way down to the smaller frigates - the sixth-raters - which might have as few as 20 long guns.

Non-Catholics generally follow the last line of the Lord’s Prayer, “deliver us from evil” with “for thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory, for ever and ever.” Catholics do not include this.

An almost throwaway line has one of the foremast jacks note of Stephen: “Physician, he is. Ain't one of your common surgeons.” This alludes to the rather lowly status of surgeons in the early nineteenth century (soon to change, as medical advances made surgery a more skilled and scientific discipline by the end of the Victorian period).

The books also explore the pair’s vices in unsparing but humane fashion: Aubrey is a spendthrift, a glutton and an adulterer. Maturin is peevish, indecisive, secretive to a fault, and stubborn.

In the books his physical courage is made even clearer - in the third instalment, HMS Surprise, he endures hideous torture in a French prison, without breaking.

I had the misfortune of first 'watching' the film aged 10 and falling asleep shortly after they got to the Galapagos, hence went through much of my life thinking it was a bit of a damp squib that didn't live up to the implicit promise of 'Maximus but on a boat'. Thank goodness I married a woman who'd watched the whole thing. It should be on the national curriculum.

I absolutely adore this film and have the complete set of horatio hornblower. Can’t wait for my boys to mature enough to watch it with me. I also recommend ‘the 13th warrior’.