The case of the implausibly slow Inspector

"The Sussex Downs Murder" and the leisurely conventions of the Golden Age

Last time I wrote about one of my favourite classic detective stories, A Murder Is Announced. This month, I want to tackle a mystery that I found quite enjoyable but flawed and ultimately unremarkable, and give some thoughts on how it reflects both the strengths and weaknesses of the genre in its interwar heyday. I’m afraid I will not be able to avoid spoilers.

The Sussex Downs Murder, by John Bude, introduces us to the Rother brothers, John and William, small-scale farmers on the South Downs. They live together at Chalklands near Washington, along with William’s wife, Janet. It is established from the very first page that there is tension between the two, and that they have very different personalities - William is sensitive and thoughtful whereas John is a hearty man of action. As the book begins, John is heading off on holiday to Harlech, in his car. But a little later, the car is found abandoned and damaged, close to Bindings Lane under Cissbury Ring, with signs of a struggle. John’s cap is on the front seat but there is no sign of John. Subsequently, parts of a skeleton are found in a consignment of lime from the kilns at Chalklands. Inspector Meredith, Bude’s usual detective - recently transferred to Sussex from Cumberland after the events of The Lake District Murder - takes charge of the investigation.

Meredith uncovers a few leads, notably rumours of a liaison between John and Janet, something at which the author hints heavily in the first couple of pages, and a mysterious man seen on the Downs at night. But then William himself is found dead, at the foot of a cliff near the Rother lime-kilns. A suicide note is on his body, confessing to the murder of John and explaining in some detail how it was managed.

Of course, genuine suicides are not common in Golden Age murder mysteries, and sure enough Meredith soon becomes convinced that William did not end his own life. A dastardly scheme is uncovered, and the novel climaxes with a tense pursuit and a written confession.

You may already be guessing the basic outline of the solution from this brief summary, especially if you have read a lot of detective stories. Long before the end of the novel, the following facts are established.

The Rother brothers, John and William, are not close and are often at odds

John Rother and Janet Rother (William’s wife) are probably involved romantically

John Rother has disappeared but there is no proof of his being dead

William Rother has been murdered, seemingly after keeping an assignation

Janet Rother has been observed behaving suspiciously at the farm at night, and has fled to London with a large sum of money inherited from her husband

A mysterious person, seemingly moving between different disguises, is at large in the locality.

It doesn’t require an especially astute detective mind to draw some pretty firm conclusions about what is going to be revealed in the denouement, especially as the main cast is fairly small, essentially just the three residents of Chalklands, and none of the supporting cast are developed enough to be plausibly connected to the crime - unless of course Bude is going to break “the rules”, by pinning the crime on someone who has not really featured in the story.

There have been various attempts to codify the informal expectations and genre conventions of classic detective stories, most famously by mystery writers Ronald Knox and SS Van Dine. But most aficionados of the genre would agree on the importance of “fair play”, i.e. the attentive reader must have a reasonable chance of identifying the culprit for themselves, which is usually taken to mean that the murderer must be someone who has featured significantly in the story, and at whose opportunity and motive to commit the crime the author has at least hinted.

The great test is our reaction on hearing the solution. Do we strike our foreheads and rebuke ourselves for being slow-witted fools who could easily have beaten the sleuth to the punch if only we’d paid more attention to the conversation about antique duelling pistols in Chapter Four - or are we tempted to fling the book across the room with a cry of “Come ON!”

As it happens, Bude could play faster and looser with these rules that many of his contemporaries, with the result that he has more than once provoked in me the latter reaction. In 1935’s The Cornish Coast Murder, for example, the killer has not really featured in the story until near the end, his identity is not really clued, and his unmasking hinges to a very great extent on facts that have not been revealed to the reader. There is simply no feasible opportunity for even a perceptive and careful reader to solve the case.

But in The Sussex Downs Murder, for the reader who trusts that Bude is writing broadly in the fair play tradition, the shape of the narrative points in one direction, and one direction only. He tries to throw sand in our eyes, but in whodunits, generally speaking, without a definitively identifiable body it is very risky to assume that a character is truly dead (I’m not aware of any method available to English provincial police forces in the 1930s by which a skeleton could be definitively identified).

One result of this lack of real mystery is that I became rather exasperated with Inspector Meredith. The amount of time he takes to understand what is fundamentally a very simple deception begins to stretch the suspension of disbelief. This affects the whole balance and pace of the book, because an awful lot of the narrative ends up feeling like busywork and padding, to disguise a slender plot.

Another great frustration - and here I must spill the beans even more explicitly, so caveat lector - is the portrayal of Janet Rother. Like several other male Golden Age authors1, Bude struggled to write compelling women (I should confess I have only read seven of his thirty-odd books, most of which remain out of print). His women, especially younger ones, tend to be fragile, emotional, easily led, and generally treated as something less than thinking, responsible individuals. In The Cornish Coast Murder, the main female character commits perjury at an inquest – a serious criminal offence which was then punishable by up to two years’ imprisonment and now carries a potential penalty of up to seven years – but it is more or less ignored, despite having badly disrupted the investigation of a murder, because her delicate female brain was under such terrible strain or some similar nonsense. Similarly, at the end of The Sussex Downs Murder, it is revealed that Janet Rother was an accomplice in the murder of her husband, and has subsequently fled abroad (John is arrested on his way to join her). But Meredith barely seems to care:

“‘I doubt if we’ll ever lay our hands on her. We’ve been in touch with the Continental police, but of course they can’t help. Too long a start, I reckon.’

[…]

‘Are you sorry?’ Meredith rubbed his chin with the stem of his pipe.

[…]

‘As a minion of the law, as the newspapers have it, I should look upon Mrs Rother’s escape as a misfortune. But sometimes the law is at war with the man, and if you asked me in the second capacity…well, here’s luck to her! We’re all misguided sometimes in life, but I reckon she was more misguided than most - that’s all!”

This is a woman who has been a willing participant in the premeditated murder of her husband, and who has lied persistently to Meredith - risking someone else being hanged for the crime - before making off with several thousand pounds belonging to her victim. Misguided is certainly one word for it. Perhaps her limited feminine faculties were simply overwhelmed! And this exchange is literally the very end of the book, except for a metafictional coda that repeats the opening sentences. The clear implication is that this is a satisfactory and fitting conclusion, and that the conscientious reader can put the work aside with a sense that justice has been done. (In other Bude books, Meredith and his police colleagues invest a great deal of time and energy in tracking down British fugitives in Europe.)

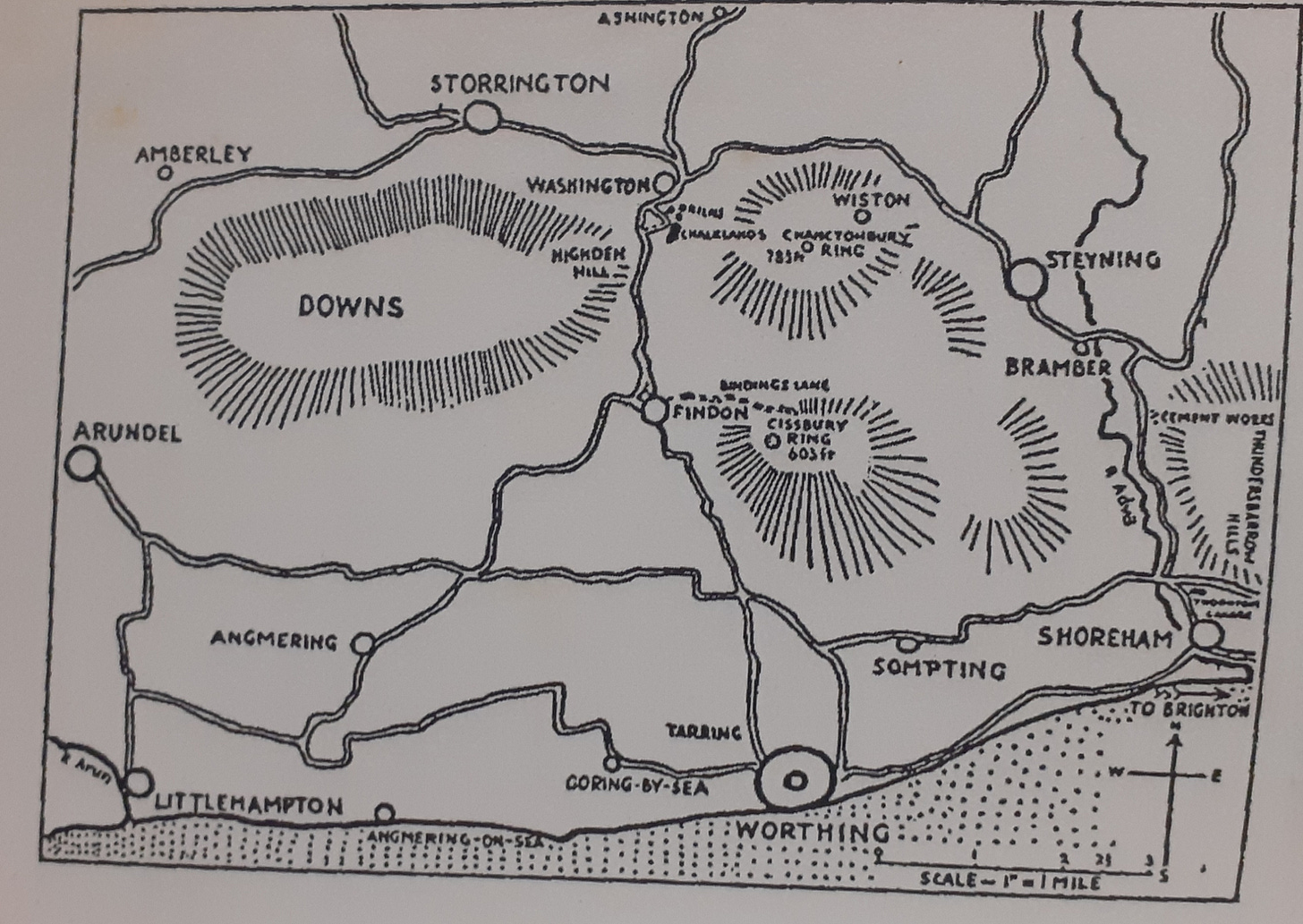

All that being said, The Sussex Downs Murder has considerable charm. The details of place and period make it an involving read, and I rather like the unhurried storytelling that is typical of this vintage of detective novel. As in Columbo, where there is pleasure in seeing how a murderer is brought to justice even when you already know his identity, it is intriguing to watch Meredith gradually gather the threads of his investigation, and close in on the villain. That Bude lays his scene in the picturesque downland along the south coast adds to the appeal. Most of the locations have at least some grounding in actual places. There really is a chalk pit close to a small isolated farm to the south of Washington; Bindings Lane is based on a real track running east from Findon. Storrington and Bramber are likewise genuine villages, albeit probably not as olde worlde as they were in the mid-Thirties. Bude’s previous mystery, The Lake District Murder, had also taken care to situate its action in a real place, specifically the small settlements to the west of Keswick. At a time when other detective novelists routinely invented whole new counties - setting books in Westshire, Midshire, Southshire or even the heroically unimaginative ———shire - it is refreshing to be able to trace character movements on a real-life map (my parents took a mini-break in Sussex a few years ago, following a Sussex Downs Murder trail they had created themselves).

This blend of old-fashioned leisurely pacing and a beautiful setting in the heart of a bucolic England yet to be marred by concrete and traffic, with an underwhelming plot and some dubious characterisation, is probably what many people have in mind when they think about crime writing from the first half of the twentieth century.

Fans and defenders can rightly point out the huge variation within the genre - in style, themes, setting, structure, characters and ideology. Raymond Postgate’s excellent Verdict Of Twelve is an explicitly Marxian novel. Dorothy L Sayers brought a literary quality to her detective stories. John Dickson Carr was a locked-room specialist, with a wild modern gothic sensibility. Richard Hull wrote darkly funny satires. Freeman Wills Crofts often set his carefully constructed mysteries in the world of commerce, industry or the suburbs, rather than rural idylls populated mainly by the gentry, the professions and the independently wealthy upper middle-class. Agatha Christie, the greatest of them all, experimented with unreliable narrators, and wrote stories featuring murder of and by children. She probed the limits of formal justice and the meaning of moral guilt. She used crime novels to examine the difficulties of living with suspicion, and the reasons why people might accept a convenient and plausible untruth rather than confront a difficult truth.

But even so, it cannot be denied that the casual critic is not entirely off the mark in his stereotype. So The Sussex Downs Murder is a useful starting point for considering the strengths and weaknesses of that type of “normal” whodunit.

An egregious example: in Freeman Wills Crofts’ The Pit-Prop Syndicate (1922), the one and only female character is a mere cipher with no personality or perspective of her own. Another character concludes that she could not possibly be involved in crime because she’s beautiful, and a central conceit of the story is that the original discoverer of the criminal scheme in the novel is so deeply in love with this woman that he will not let his fellow amateur investigator go to the Yard because it might cause her to be ashamed of her father, who is involved. No-one seems very bothered that this refusal leads to the father being killed!

This is the book I'm reading at the moment! I'll read your thoughts once I get to the end

Great read as ever!

That sinking feeling when you realise what you thought was too obvious, and plainly a red herring , turns out to be the actual solution. Aargh.

The worst of those for me was ‘Swan Song’ by the usually reliable Edmund Crispin. I think what happens is the author gets so tangled up they don’t notice, and they fail to cover up with a clue blizzard. Dickson Carr and Christie bombard you with so much information that you don’t have enough clear space to connect up the chain.